Six months into editing our Ukrainian resistance documentary, I hopped on my weekly Zoom with the director Alex LeMay. He’d just screened our rough cut at Notre Dame for a small audience, and the feedback wasn’t what we’d hoped for.

“They loved it overall” he told me. “But our Hero’s Journey structure isn’t working.”

Creative Force is a documentary about artists using their skills to resist the invasion of Ukraine and we had reached an inflection point. After three years of production, we thought we had our story. We didn’t.

But this failure became the most valuable part of our entire process.

We’re currently at the crucial junction between completing our festival cut and beginning the finishing process (color correction, sound design, and motion graphics – all to be handled by Ukrainian team members who will bring their unique perspective to these final elements). This week also marks a significant milestone as we will receive word from our first festival submissions.

THE REALITY CHECK

Our initial approach followed the My Octopus Teacher model, which involved using director Alex LeMay as the audience’s guide into war-torn Ukraine (which we kept part of). Early screenings confirmed this was effective. Alex served as a crucial entry point and reference for audiences exploring an unfamiliar world.

We started with a classic Hero’s Journey structure, focusing on one man’s quest to deliver supplies to the front line. It worked in theory. We had our guide, our hero, our journey. But here’s what we discovered:

Ukraine’s resistance isn’t one person doing something great. It’s all of the people, each finding their own way to fight and resist.

The audience wanted to spend more time with the people of Ukraine. They wanted to explore beyond our main character Rostyslav and meet the countless others we’d interviewed. The feedback was consistent. The feedback was clear. The feedback was devastating.

I tried restructuring within the Hero’s Journey framework. I attempted to give other characters more time while maintaining the single-hero focus. I wrestled with transitions and pacing.

Nothing worked.

Honestly? I was at a loss. I had no idea how to restructure this massive amount of footage into something that honored these voices. So I did something that felt completely wrong for a filmmaker on deadline:

I took a week off. And that break saved the project.

During my time away, I hopped on the phone with an editor friend who gave me what now seems like obvious advice:

“Just use titles to map out the empty sections.”

I also attended an event where someone recommended I watch Buena Vista Social Club.

This led to my breakthrough:

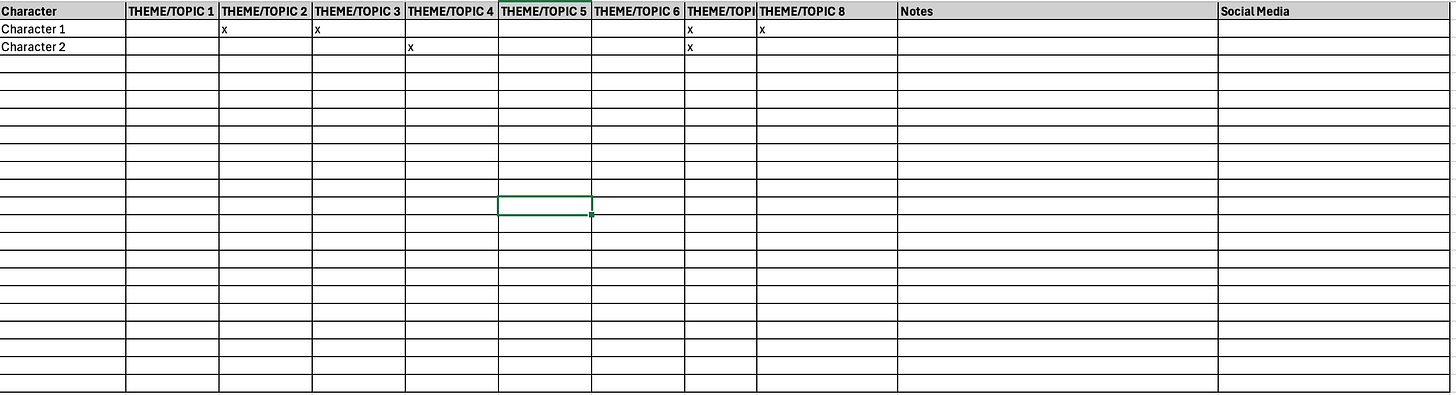

I created a Story Matrix.

A spreadsheet with all interviewees listed vertically and thematic/story categories horizontally. Instead of looking for what fit my predetermined narrative, I checked off each person’s connection to themes like giving food, resistance, and art.

Here’s a concrete example of what this revealed:

I had interviewed a pianist who played during air raid sirens to inspire people coming to Lviv. Through the matrix (and watching the footage), I realized I could use the sound of sirens to connect his story to the director’s nighttime experience and then transition to another musician: a woman who teaches others to sing Ukrainian folk songs. Then sending those to soldiers on the front lines.

The sirens became both warning and inspiration. The matrix showed me connections I’d never seen.

Our film became a marriage between Buena Vista Social Club’s character vignettes and My Octopus Teacher’s journey structure. Each new person would build upon the previous while exploring different aspects of Ukrainian resistance.

Lessons For Fellow Creators

- Don’t rush the process, and don’t be afraid to stop. There’s a rule of thumb for documentaries:

1 month per 10 minutes of final film.

We found this to be true. But here’s what they don’t tell you – sometimes you need to step away completely. After 6 months on our first edit, we spent a month gathering feedback, then another 8 months restructuring.

When you’re stuck, truly stuck, take a break.

The answer often comes when you’re not actively searching for it.

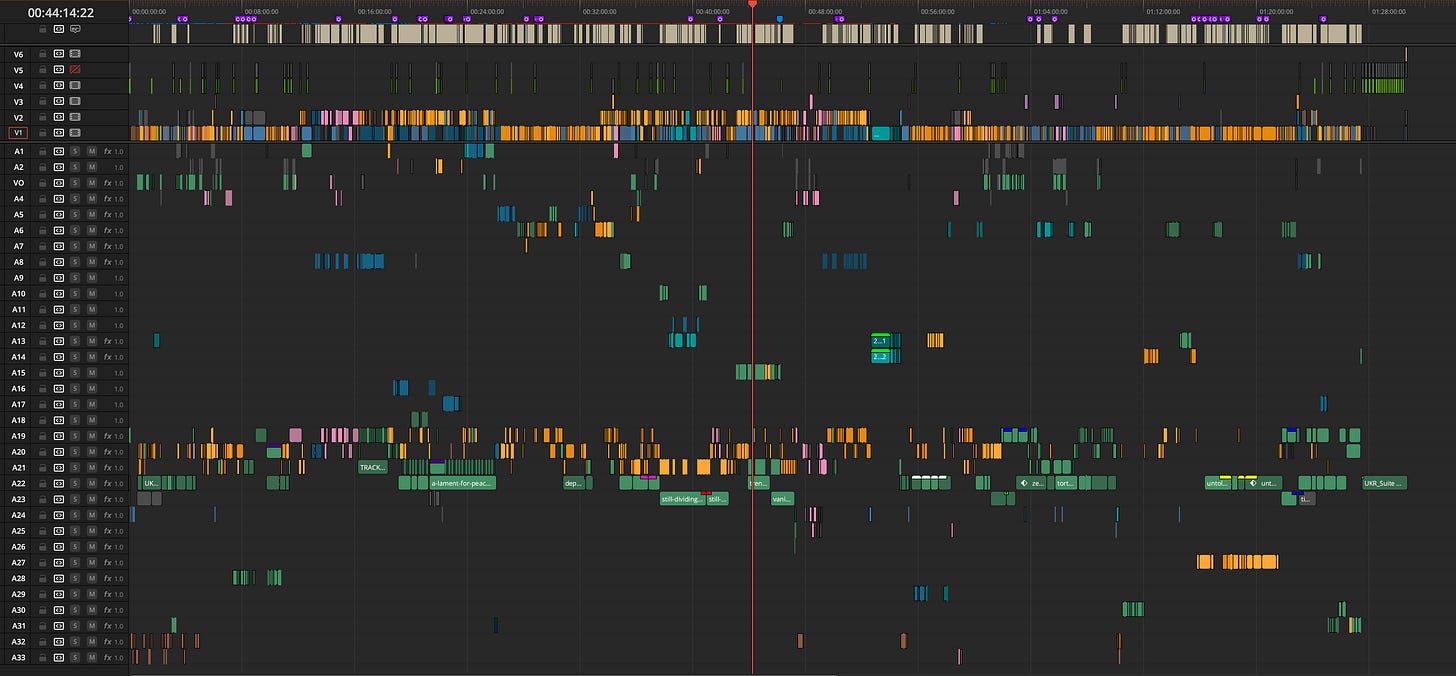

- Create systems, then trust them. For documentaries with multiple characters, create a Story Matrix (or your version of it). Watch all interviews and identify emerging themes and patterns. Find your reference films. Use titles on your timeline as placeholders (great advice from The Jinx Part 2 editor). Don’t be afraid of whiteboards, post-it notes, anything that helps you zoom out and see the complete story. The matrix will show you connections your brain missed.

- Let the footage speak, then listen to the right voices. Documentary editors are writers. We dive into footage and discover what story is taking shape. But we also need feedback. Listen to your collaborators and audience when patterns emerge, but make sure you’re getting input from the right audience. If you know who the film is for (which you should know before shooting), then you know who to listen to. Our breakthrough came when we realized we weren’t just making a film about resistance:

We were making a film that needed to resist the very storytelling structures that would diminish Ukrainian voices.

LOOKING AHEAD

Our immediate priority is completing the finishing process with our Ukrainian collaborators, who will bring their perspective to color correction, sound design, and motion graphics. Since we edited in Resolve, the handoff should be seamless.

We’re also waiting to hear back from our first festival submissions and by the time this publishes, we should have initial responses. We’re working both paths simultaneously, which is standard practice as festivals understand filmmakers are often still finishing their films before screenings.

This film has taught me something beyond filmmaking technique: the importance of putting my own ideas away and just listening. Listen to what’s being spoken by the people you’re interviewing and do your best to represent them within the confines of a 90-minute piece.

I honestly wish there was time for all the stories we experienced. But there’s only so much you can ask of an audience.

The truth is, this lesson extends far beyond editing. Our world would be better if we all took time to step back, create space, and just listen.

Now is the time to let the stories speak for themselves.

Production Stats:

- Timeline: 3 years total (shot 2022-2023, post-production July 2023-July 2025)

- Team morale: Invigorated after recent Ukraine screening and seeing how moved audiences were by their own story

- Biggest win: Entering festivals with confidence in our story and structure. Everyone who’s watched is inspired to help.